ARTICLE SUMMARY

Human-centric automation promises to liberate people from redundant and repetitive tasks so that they can invest their time in more meaningful work.

Money is often the driving force behind automation. In a holistic business strategy, however, automation can also serve a higher purpose. That’s what the concept of human-centered automation is all about.

Spoiler: it might not even bring about a robot apocalypse.

Read the report No-code Automation: Good for Business, Great for IT

Does automation doom us to a dark fate?

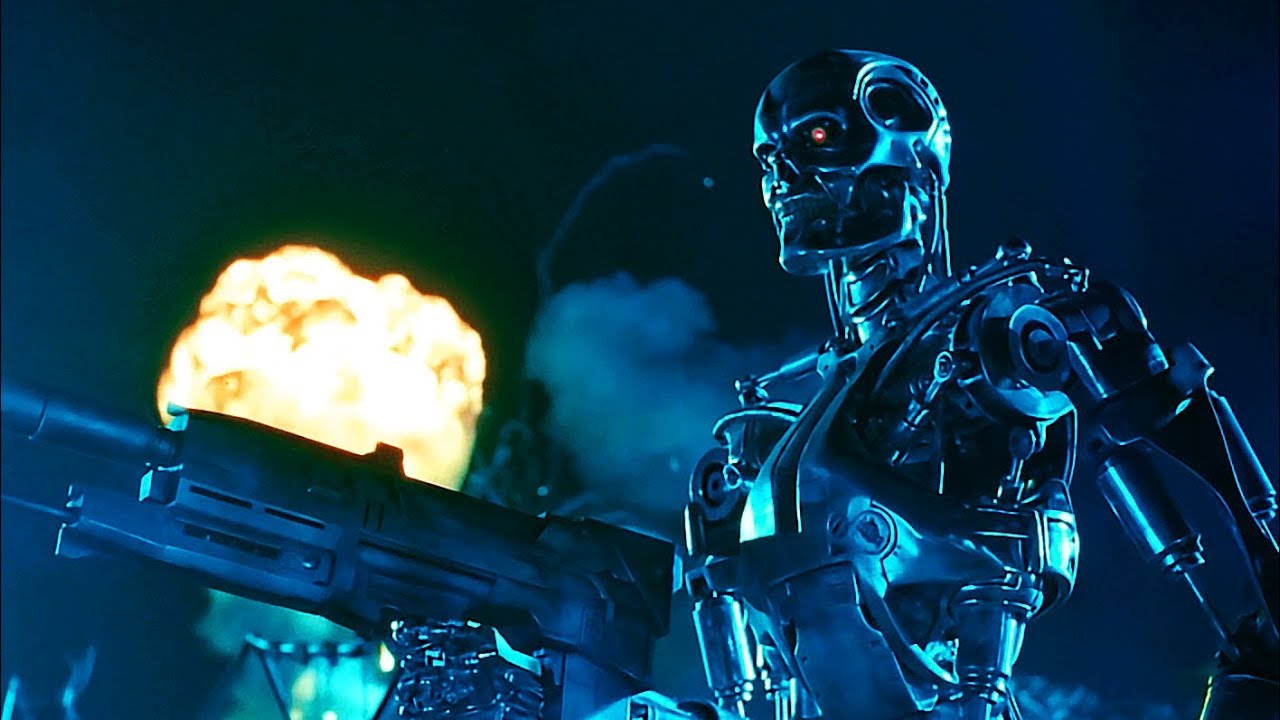

One of the recurring themes in the Terminator film franchise is people having the power to shape their futures. The notion that human agency can prevail over perceived destiny is best illustrated in a deleted scene from the 1984 film in which Sarah Connor (portrayed by sci-fi legend Linda Hamilton) tells her protector (a time traveller from an apocalyptic future) that “there is no fate but what we make for ourselves.”

If you aren’t familiar with the Terminator films, they are worth your time. (The 1984 and 1991 installments are, anyway. The others are debatable.)

Without giving away too much, the core narrative of the films is this: at some point in the future, machines become so advanced that they gain sentience. As a result of becoming self-aware, they conclude that humans are a threat and that they (meaning we) must be eradicated. That’s the dark fate referred to in the title of the most recent film: a future in which machines declare war on humans.

One of the most satisfying aspects of the series is the way the writers develop the relationship between humans and machines over the course of the story. In the first film, machines are one-dimensional antagonists with a single purpose: hunting humans to the point of extinction. In Terminator II: Judgement Day (read: one of the best sci-fi films ever made) and Terminator: Dark Fate, the writers explore alternative scenarios in which the relationship between humans and machines is more complicated.

In the later films, we see machines acting as protectors and helpers of humans, as well as their adversaries.

Thematically, there are two important takeaways from these films. First, the relationship between humans and machines is always going to be complicated; and second, we have agency in determining how we relate to machines — and how they relate to us.

That’s what this article is about.

Human-centric automation considers this relationship between humans and machines, and imagines a future in which we keep the human part of the equation front and center. Human-centric automation allows us to develop automations that help rather than harm.

Automation is nothing new

Throughout history, people have sought opportunities and developed technologies that allow us to increase the value of our work or make better use of our time. The inventions of the wheel (3500 BC in Mesopotamia), the movable type printing press (likely c 1000 AD in China), and the mechanization of the automobile assembly line (1946, Ford Motor Company) are all examples of ways we have used some form of automation to make our work easier, more efficient, and/or better organized.

In recent years, automations have become more complex, and the rate of automation has increased exponentially. The introduction of the microchip, personal computer, and cell phones have made it possible to automate tasks, workflows, and processes in ways that were once unimaginable. We have become so used to the experience of automation that we no longer ask ourselves why we do it.

Why automate? (For that matter, why even work?)

The short answer is that automation creates value.

This value is usually understood in terms of money: automation speeds up production, expands capacity, and maximizes efficiency — all of which increase revenue and drive profits. In this sense, automation creates value by helping us meet financial goals. That’s a perfectly rational motive for the development and implementation of automation, but automation can have other aims.

Automation, like labor, is about more than the financial value it creates. In his introduction to Working, Studs Terkel describes labor this way:

“It is about a search, too, for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying.”

Labor isn’t just about earning money, and work isn’t just about toil for the sake of financial reward. Most of us want to work — at least in part — in order to make a meaningful contribution to the world. We work because we want to have an impact. We work in order to satisfy our sense of purpose.

Automation plays a critical role in bringing this kind of meaning and satisfaction to our work. It does this by unburdening us from mundane tasks and repetitions that prevent us from unlocking our true potential. Automation liberates us from drudgery so that we can engage in the work that matters to us. Automation creates value for us by giving us more control over our time.

Human-centered automation

Most of us default towards a cost-driven model of automation because the results are easily quantifiable, quickly attainable, and immediately rewarded. However, once we stop seeing automation as only an opportunity to contain costs or increase revenue, we begin to get a sense of its potential for generating more comprehensive benefits within a holistic business strategy.

An alternative is to take a “human-centric” or “human-centered” approach to automation. Instead of focusing only on increasing efficiency or revenue, this model of automation considers what an automation means for people.

Within a human-centric approach to automation, managers may:

- Consider the long term effects of automation on people (job satisfaction, employee experience, stress levels) versus any short term gains.

- Modify workflows and tasks in order to provide the best user experience, whether that means an employee or customer

- Organize work so automation relieves workers from boring or repetitive tasks, allowing humans to focus on more complex and interesting work.

What is human-centric automation?

In order to crystallize what we mean by “human-centric automation” and why it’s important, we need to dig into both parts of the term: “human-centric” and “automation.” The best way to do that is to look at how these terms have been defined and how they are being used. We’ll begin with the easy part: automation.

The automation part

“Automation” can be a mushy term. It’s a word many of us play fast and loose with as we describe a wide range of activities and technologies, from the highly complex (such as artificial intelligence automation) to the relatively simple (such as vacation response in our email).

IBM provides a succinct definition. According to them, automation “is a term for technology applications where human input is minimized.” In other words, automation conserves human time and energy.

When we use the term “automation,” we are referring to the specific instances in tasks, workflows, or business processes that can be performed by a machine or software application. As a result of automation, we create a surplus of time and energy that can be directed to other, more important work.

The human-centric part

Defining “human-centric” is more complex. That’s because 1) there are a few similar terms in use that don’t share precisely the same meaning and 2) we need to understand the difference between an automation that is human-centric and an automation that is not human-centric.

In order to understand what it means to be “human-centric,” we can start by considering the field of human-centered design, as well as related terms and how they have been defined by experts in engineering.

Human-centered design

“Human-centric” can be thought of as a relative to the discipline of human-centered design (HCD). HCD is an approach to problem-solving that emphasizes the human perspective of both the problem and the solution. In other words, HCD prioritizes human experiences, needs, and objectives throughout the design process.

In his 2008 essay “On Human-Machine Symbiosis,” engineer and author Mike Cooley provides an elaborate definition of human-centeredness. According to Cooley, “human-centered”:

| Asserts that “we must always put people before machines.” |

| Is a “symbiotic relationship between the human and the machine in which the human being would handle the qualitative subjective judgements and the machine the quantitative elements.” |

| Involves the “radical redesign of the interface technologies…which would support human skill and ingenuity rather than machines which would objectivize that knowledge.” |

In Cooley’s view, a human-centered design prioritizes the needs of humans and organizes work so that the work done by machines complements and enhances — but never competes with or diminishes — the skills and abilities of people.

ISO definition of human-centered design

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is a global, non-governmental organization that sets a wide range of standards that govern science, manufacturing, healthcare, food safety, etc. in many countries. From the perspective of creating computer-based interactive systems, they describe HCD this way:

Human-centered design is an approach to interactive systems development that aims to make systems usable and useful by focusing on the users, their needs and requirements, and by applying human factors/ergonomics, and usability knowledge and techniques. This approach enhances effectiveness and efficiency, improves human well-being, user satisfaction, accessibility and sustainability; and counteracts possible adverse effects of use on human health, safety and performance. ISO 9241-210:2019(E)

In this sense, HCD means building software that serves human interests and augments human knowledge and skill. It also means that these interactive systems should have a positive effect on “human well-being” and “user satisfaction.” This last point is important because it means that to be human-centered, it’s not enough for a design to be neutral. A human-centered design must also help people.

Human-centered automation

Finally, the science of mechanical engineering defines the related concept of human-centered automation. This definition is provided in the context of designing aircraft navigation systems, and it provides an important vantage point from which we can start to understand the value of human-centered design. According to Christine M. Mitchell, human-centered automation refers to:

The use of automation technologies (e.g., intelligent aids, displays, warning devices) to enhance the capabilities and compensate for the limitations of human operators responsible for the safety and effectiveness of complex dynamic systems. She also notes that “human-centered automation is automation whose purpose is not necessarily to automate previously manual functions (i.e., gear shifting), but rather to enhance user effectiveness and reduce error.

Those two sentences are doing a lot of work. Let’s see if we can unpack them:

According to Mitchell, automation acts in a complementary role to humans. Automation capitalizes on machines’ consistency, timeliness, and immunity to distraction. Humans are then free to monitor for and manage unpredictable or complex events.

In Mitchell’s example, that looks like an aircraft navigation system in which some tasks are managed through automation so that pilots can focus on the overall safety and success of the flight. Put another way, automation makes it possible for humans to do the most important work, including being available to handle any emergencies that arise.

Finally, one very human-centric question raised by this perspective: what happens if humans forget how to handle a process because it’s been automated? In the aircraft example, that means thinking about what happens if a system fails and a pilot has to take control of a task or function that has been automated for so long that it’s now foreign to them. That kind of forward-thinking is exactly the earmark of human-centric automation.

No automation for the sake of automation

In light of what we now know about human-centered design and human-centered automation, we can see that human-centric automation is essentially similar in nature. Simply put, it is automation that benefits humans. Instead of automating processes, workflows, or tasks just because they can be automated, a human-centric approach begins with the questions 1) should this be automated? and 2) how will this automation impact people?

We can also build out a more thorough definition of human-centric automation in terms of processes, workflows, and tasks. For example:

| Makes use of technology to conserve human time and energy |

| Improves user experiences by eliminating repetitive or meaningless work |

| Enhances human skill and compensates for human limitations |

| Complements — rather than competes with — human efforts |

| Benefits workers by improving working conditions |

| Liberates humans from drudgery |

Beyond efficiency: automation is about liberation

A holistic business strategy relies on automation for more than just the relentless pursuit of efficiency. A long-term strategy sees automation as an opportunity to reshape processes, workflows, and tasks so that they make work better for people.

Human-centric automation frees us from frustrating, repetitive tasks and creates a surplus of human time, energy, and ingenuity. Then it’s up to us to direct that surplus toward solving complex problems, thinking creatively, and generating value for the enterprise in ways that have not yet been imagined.

If we approach automation in this way, by always prioritizing the human element of the equation, we can create a future of work in which automation helps rather than harms. As Ms. Connor once told a man from the future: we have no fate but what we make.